For the Term of your natural life

Remember the good old days? When you could put your money with a bank and receive a real return? That simple experience is drifting further and further away from Australian investors today. Interest rates continue to fall and the press celebrates the effects on borrowers, forgetting about Australian savers and investors who rely on interest income to live. What’s more, banks are now putting more and more barriers around those deposits. The term deposit game is genuinely changing.

Term deposits in the global financial crisis…

As we’ve previously written, much of what is currently occurring with term deposits can be better understood if we first reflect on the events of the global financial crisis (GFC). On 15 September 2008, Lehman Brothers, one of the oldest and largest investment banks in the United States, collapsed and filed for bankruptcy as a direct result of its investment in highly complex, derivative assets. This was the symbolic epicentre of the GFC and was followed by years of dislocation in markets and economies across the world.

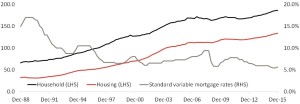

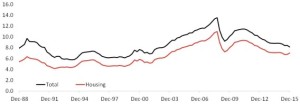

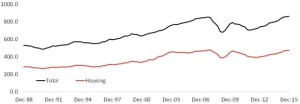

The Australian financial system had substantial potential exposure to the effects of the GFC. Our major banks were funding less than half of their balance sheets from domestic deposits and were heavily reliant on international financial markets. The GFC sent shockwaves through these markets, as the world’s banks wondered nervously which of their counterparties would become the ‘next Lehman Brothers’.

The response from the Australian government came on 12 October 2008, when it announced that it would guarantee deposits made with Australian banks. In effect, it was telling the world that – even if an Australian bank became the next Lehman Brothers – the Australian government would ensure that depositors would be repaid in full. This guarantee covered both wholesale deposits (until 31 March 2010, when the wholesale scheme closed to new liabilities) and retail deposits (currently still in force, but only to a total guarantee of $250,000 per retail account).

Simultaneously, the Australian banks reacted to reduce their exposure to the international money markets that had proved to be so vulnerable to panic. Their primary tool was the offering of higher interest rates on deposits. This ushered in a golden period of deposit interest rates for Australian investors. Each day it seemed that a new bank was offering a new interest rate special. Even as the official cash rate decreased in response to the economic effects of the GFC, bank deposit rates continued to climb. At one point, it was possible to secure a five year fixed term deposit rate at major Australian banks for 8% p.a. Times were good indeed.

… and the inevitable decline…

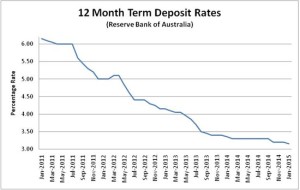

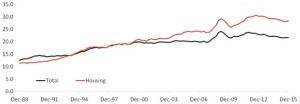

Of course, this was all too good to last. The banks were successful in rebalancing their funding mix and retail deposits had become a very expensive source of funds. In response, they began to reduce the rates that they were paying their depositors. This process was inexorable and largely independent of movements in the official cash rate. Indeed as the following graph shows, the story of the last four years has been the story of the reduction in retail deposits rates.

The situation for term deposit investors is now dire. Rates are barely positive in real terms – meaning that investors are struggling to keep up with inflation, let alone to generate surplus income on which to live. What is more, consensus projections for interest rates are that – far from recovering – interest rates are likely to remain stable or even decrease further in the months and possibly years ahead.

New regulations making it harder for term deposit investors

The Australian government and banks were not the only institutions reacting dramatically to the GFC. In Basel, Switzerland, the world’s oldest international financial organisation, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) coordinates discussions between the world’s central banks (including our own Reserve Bank of Australia) in an endless quest for financial stability. The BIS hosts the highly influential ‘Basel Committee’, which is the primary global standard-setter for prudential regulation of banks.

The Basel Committee’s responses to the GFC came in the form of a comprehensive set of reform recommendations known as ‘Basel III’ (superseding the Basel II regime). These recommendations affect how banks manage their capital and liquidity. And these recommendations are affecting Australian term deposit investors right now.

Many investors have already informed us that they have received unusual notices from their bank. As term deposits come up to maturity, many banks have been writing to their depositors to notify them of ‘new terms and conditions’. In short, the new terms and conditions generally require that investors give 30 days’ notice to banks if they wish to take out money from a term deposit before maturity. Sitting behind this change are the Basel III liquidity requirements that seek to ensure that banks have stable and liquid funding structures to deal with any future financial crises.

Whilst these regulations may be sensible from a financial system point of view (and our view is that they are), they are just another obstacle for poor, battered term deposit investors.

What are the alternatives?

Given all of this, it is hard to see a sensible case for substantial exposure to term deposits for most investors. Whilst they are a good source of capital protection, their low rate of return means that portfolios will, at best, just keep up with inflation.

Therefore, investors are forced to look further for income producing investments. Bonds are a traditional option, but there are fears that they are experiencing a price bubble that could burst at short notice, leaving investors with substantial capital losses. Hybrid notes have been popular in some circles, but their complexity makes them unsuited for most investors.

Then there are equities. This has been a very popular strategy for some years, as investors chase dividends and franking credits. But with many analysts assessing the Australian stock market as over-valued, capital value remains at risk.

Source: Randal Williams, Chief Wealth Management Officer & Chris Andrews – Head of Funds Management, La Trobe Financial Asset Management Limited